As of 11 May, our Covid-19 forecasting system started consistently predicting a coming rise in cases for the UK, driven largely (as it turns out) by the Delta variant of the Covid-19 virus. In the UK this has almost certainly been facilitated by both the general relaxation in lockdown and by events such as the G7 Summit and the Euro 2020 competition. So far, so bad.

Other factors though are far more hopeful – we are seeing a very significant decoupling between case rates, hospital and ICU admissions and in particular death rates. This does demonstrate that the game has changed, and that we need to be rethinking our approach to managing our way out of the pandemic.

That said, government policy in many places still appears to be conditioned by the assumption that the vaccines effectively eliminate transmission, something that simply has not been demonstrated.

Uncoupling the Consequences

In our internal systems, where we test and validate new analytics before releasing them publicly, we\’re now seeing data that entirely supports the now widely reported change in the relationship between cases and hospitalisations, and between the latter and subsequent ICU admissions, and overall mortality.

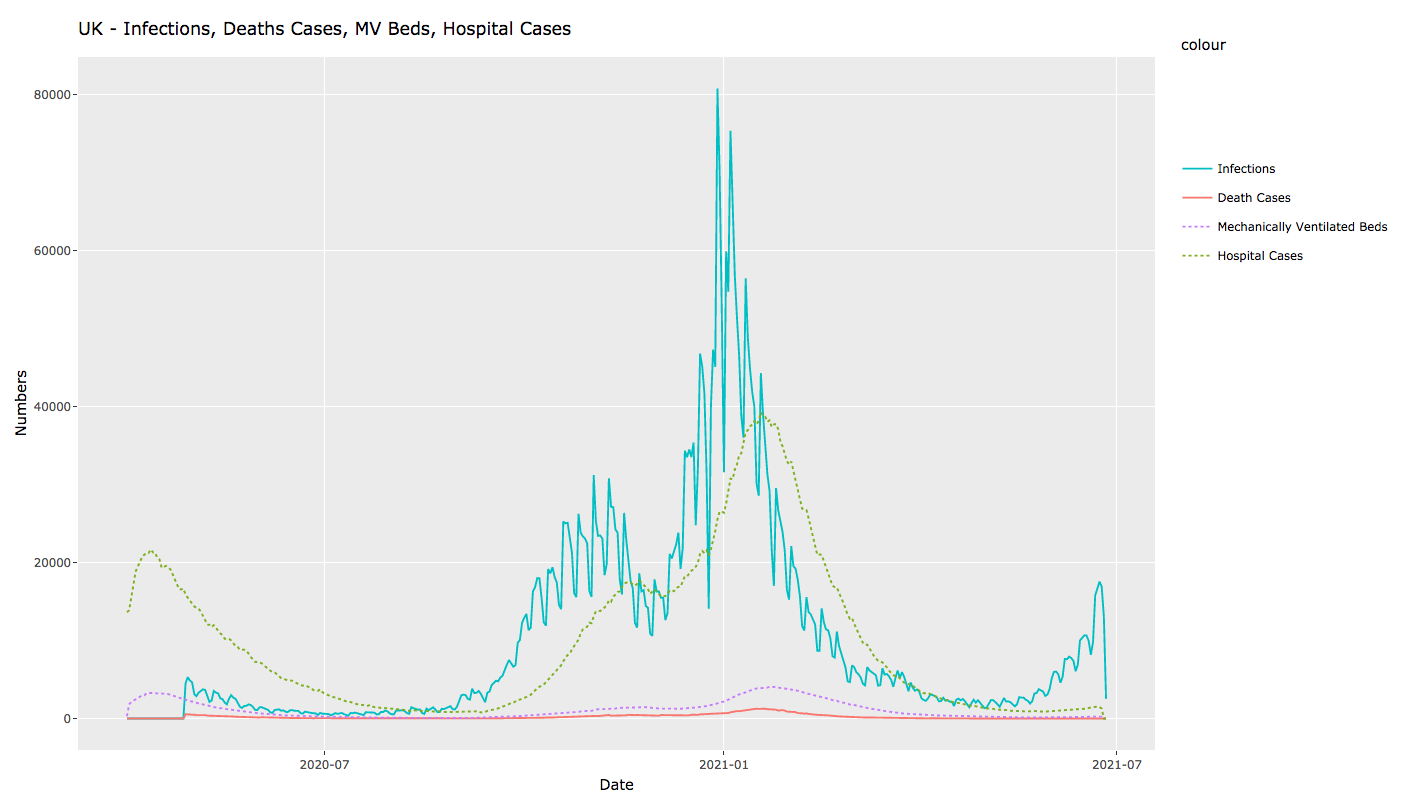

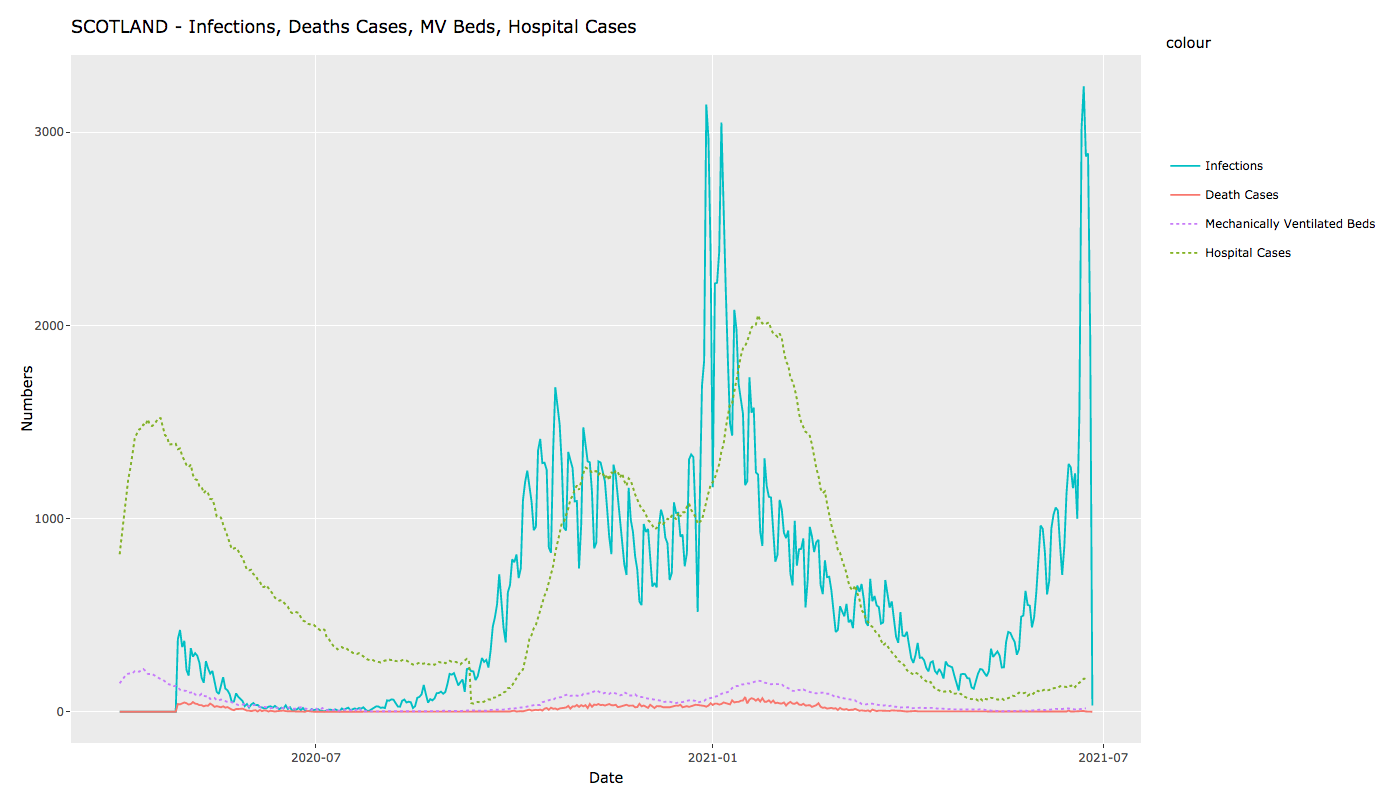

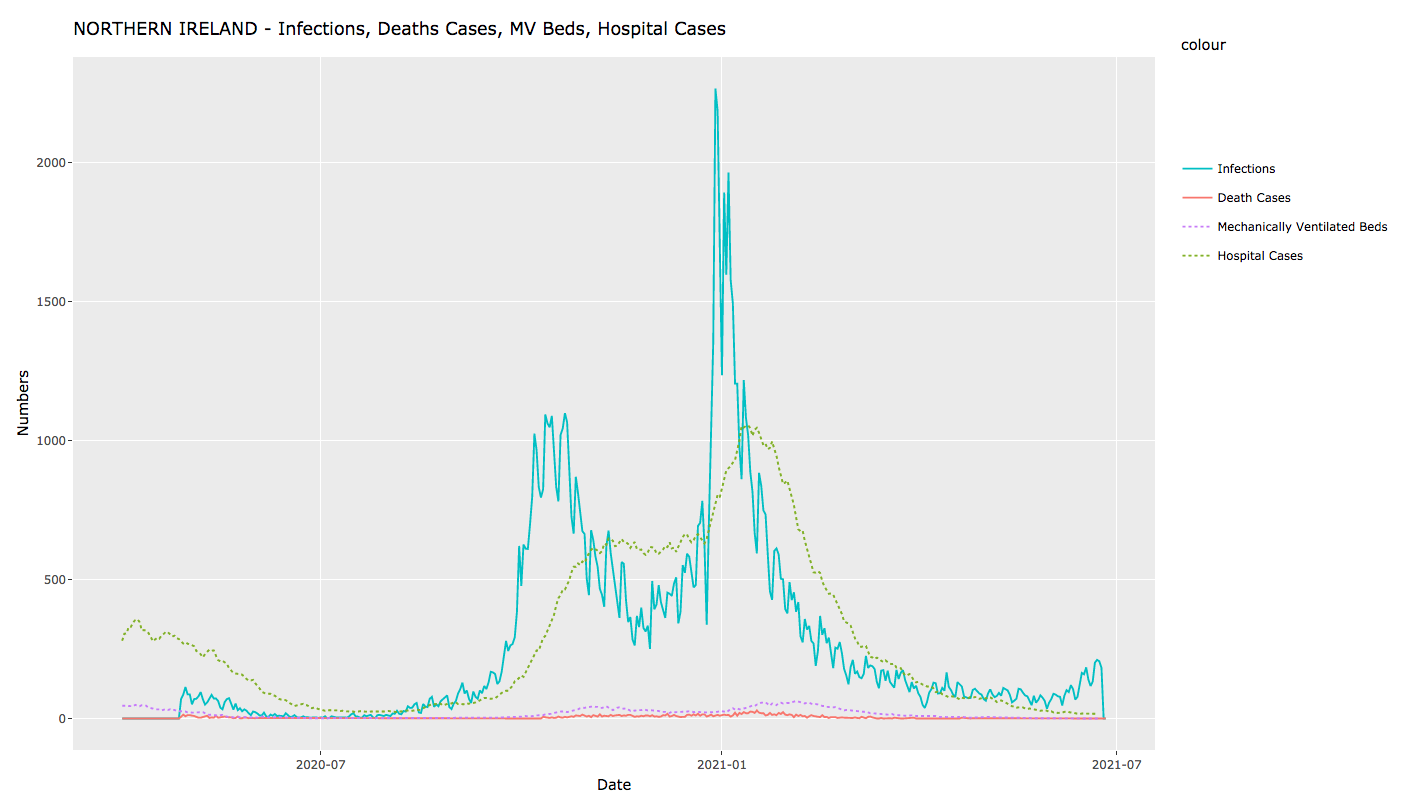

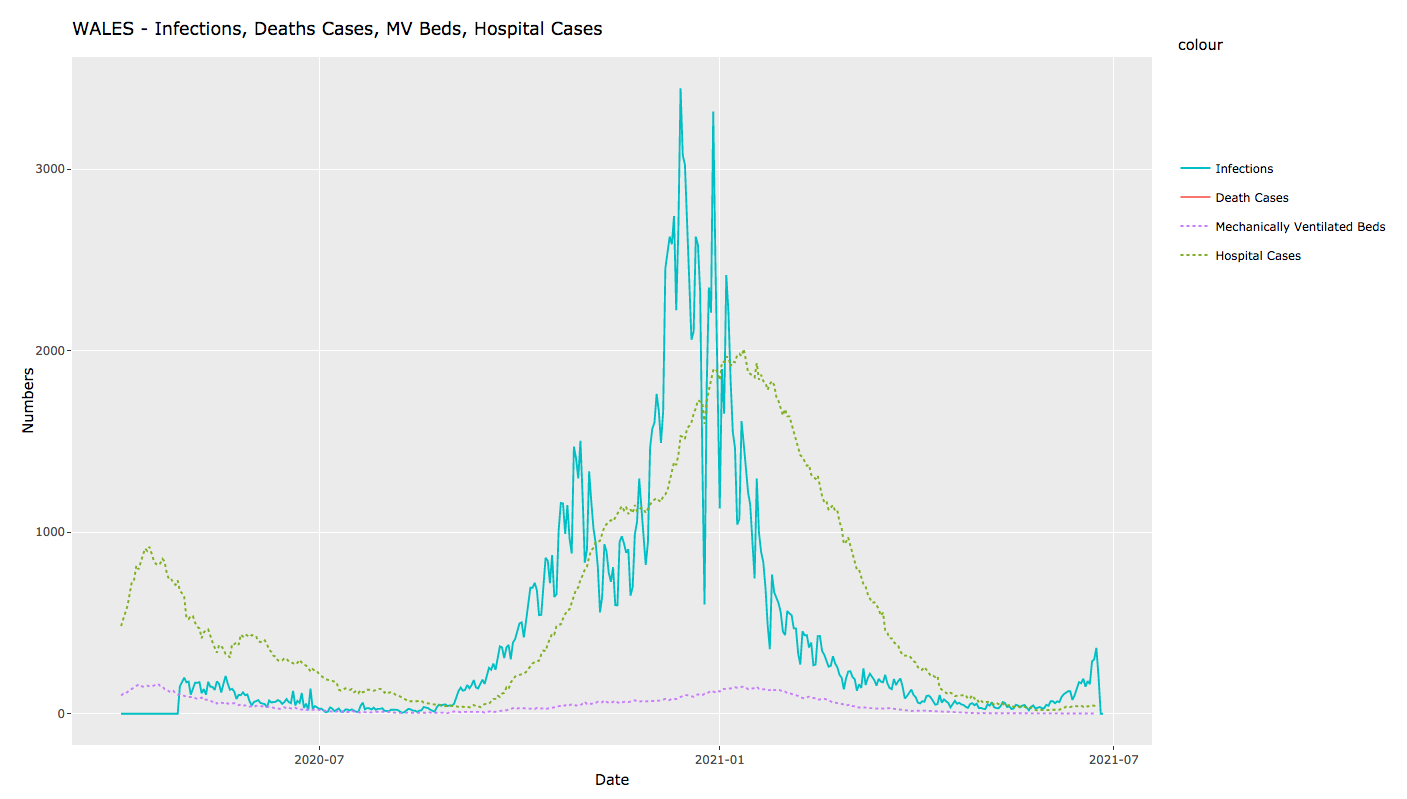

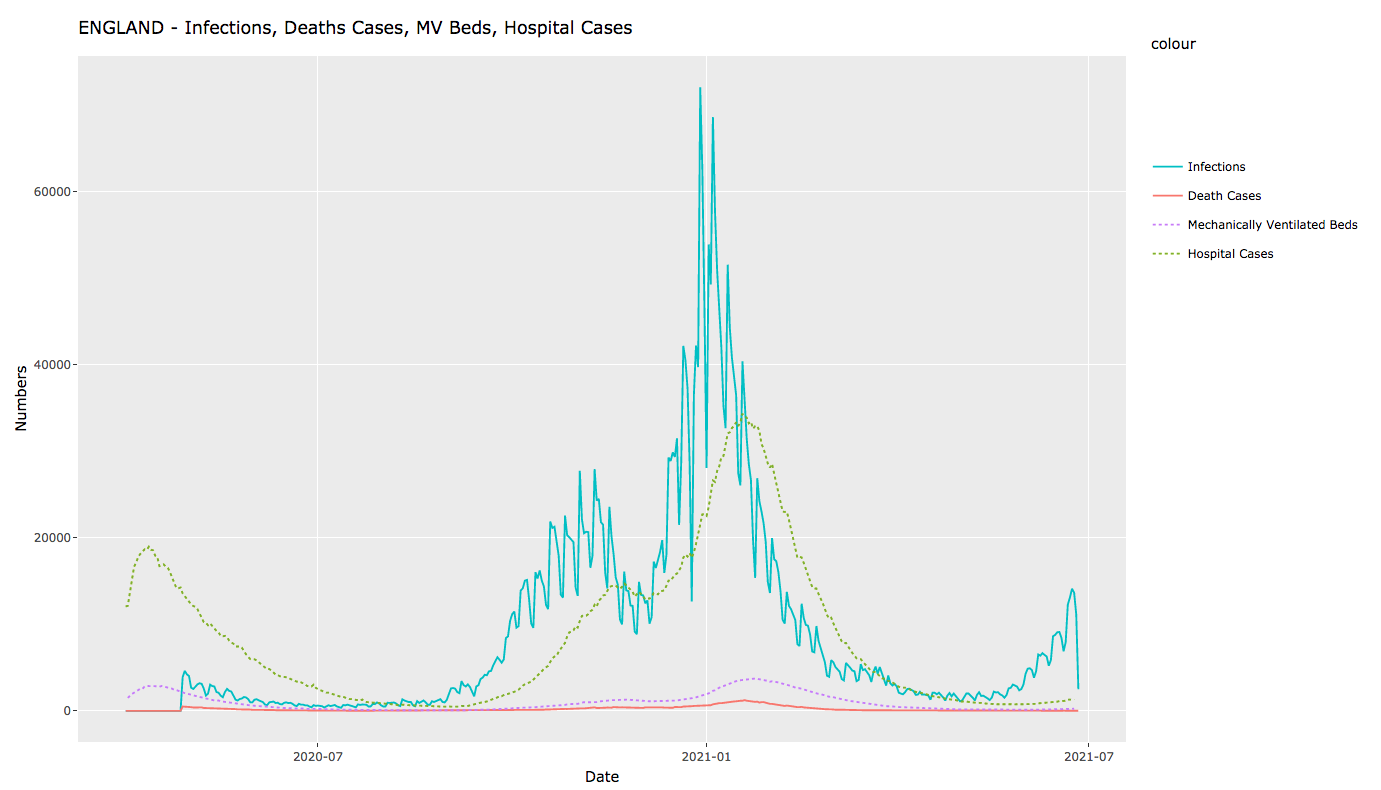

Hospital admissions are, for the first time, not tracking the rise in cases. And occupancy of beds with mechanical ventilation is, likewise, not rising in the line with cases. Deaths then, as you\’d expect, are in turn not tracking case numbers to anything like the same extent as previously. The graphs below show the latest available figures, respectively for the UK, Scotland, Northern Ireland, Wales and England.

In all cases, we\’re seeing a very significantly lower degree of hospitalisation and consequent mortality relative to case numbers.1

This is, for the moment at least, extremely good news, to the point where we should be starting to rethink how we regard the pandemic, and how we manage it. However, we also know that death cases, hospitalisation and beds with mechanical ventilation are following increasing infection numbers with a lag of about 10-14 days. Therefore the next 2-3 weeks will give a much better picture on those numbers. At present we are seeing that apparent level of uncoupling of severe symptoms from increasing infection numbers. So let\’s start with the reasons for this welcome decoupling:

The Why

Obviously the biggest single factor is the vaccination programme, where most of the main vaccines appear to be 66-94% effective in fully suppressing symptomacity with current variants. So none is 100% effective, but all drastically reduce whether symptoms appear at all or, if they do, the likelihood of being hospitalised.

Then there\’s the simple and brutal fact that, due to the repeatedly ineffective responses of governments to the pandemic, many of the most vulnerable have already died. Of the G7 economies, the UK currently sits second on the league table of shame for per capita deaths, cumulatively, 191 per 100,000 population, behind only Italy, who were hit by the first wave weeks before the UK. For reference, Germany is currently at a cumulative 109 deaths per 100,000 population.

Finally, of course, those who have had Covid-19, whether or not showing symptoms, have at least a degree of naturally acquired immunity, with the caveat that studies suggest that this may taper off after 4-6 months.

Other Factors

There is still a surprising dearth of validated studies on just how effective any of the Covid-19 vaccines is at reducing transmissibility in an exposed individual (rather than reducing symptomacity and subsequent hospitalisation, where the data is pretty good). By the very nature of a live pandemic, much published data is either anecdotal or at the preprint stage, without full peer review. Little appears to have changed here since we last reviewed the situation in March, when we saw that:

- An oft-cited Israeli meta-study (still in preprint) showing a positive impact of vaccines on transmissibility appears to have a poor and inconsistent methodology, from which it is very difficult to draw conclusions with any confidence. It\’s provisional findings were that, after vaccination with the Pfizer/BioNTech mRNA vaccine, that the viral load was reduced 4-fold for infections occurring 12-28 days after the first dose of vaccine, with an obvious impact on the likelihood of onward transmission.

- A Scottish, record-based linkage study, again in preprint, included 144,525 healthcare workers and 194,362 members of their households. This analysis showed that household members of healthcare workers vaccinated with a single dose of either Pfizer or Astra Zeneca COVID-19 vaccine were at significantly reduced risk of PCR-tested infection 14 days after vaccination. The study reported a 30% decrease and notes that this is probably an underestimate, suggesting that the decrease could, in reality, be up to 60%. This paper also lacks detail as to Materials and Methods, so should be treated with the same caution as any meta-study.

- One paper that is fully reviewed and which we regard as being as close to authoritative as any, is a US paper claiming that vaccination my not prevent nasal SARS-Cov-2 infection and asymptotic transmission. The main argument comes from the fact that in general systemic respiratory vaccines provide little protection against viral shedding and, thus, transmission of the disease. The current SARS-Cov-2 vaccines are producing an IgG response whereas in order to reduce viral shedding within the airway would require a mucosal secretory IgA response – in other words, from different sets of immune response.

Given that we haven\’t yet seen a truly valid study on the subject, it\’s probably reasonable to say that the vaccines likely do positively impact transmissibility but that this effect is of a lower order than their impact on symptomacity and that both factors remain significant in a vaccinated population.

The genuinely frightening element here is that governments in many places are formulating policy as though vaccinated individuals can be treated as non-transmitting, with strong collusion from most media outlets. The fundamental paradox here is that the incidence of vaccination may, along with the relaxation in restrictions, be a large factor in driving the current case numbers, with the vaccines creating a large cohort of asymptomatic carriers of the virus.

This then suggests that we do now have a \’superspreader\’ situation, albeit with far lower health implications for most people than hitherto in the pandemic.

We are also at the stage where the virus has become endemic – it, and it\’s emerging variants are not going away, so we need to either maintain levels of restriction that are no longer necessary in health terms for the broader population or to accept that a return to normality needs to be accompanied by a continuing cycle of vaccine development and inoculation, much as we see with the the annual \’flu\’ vaccination. That of course would need to be accompanied by careful monitoring of both declining immunity over time and the impact of new variants as they emerge. There, the general evolutionary trend of an RNA virus is to become more infective but less lethal, but that doesn\’t exclude either a \’wildcard\’ mutation that is more lethal or any variant being able to partially or wholly circumvent naturally- or vaccine-acquired immunity. The latter is however far more likely.

The Vulnerable

Firstly, the vaccination programme is not yet complete. Across the UK, as of 24 June, 43.7M people have had a first dose, and 31.9M a second, out of a population of 66.7M. So there we\’re still at the stage where more than half the population still doesn\’t have the protection of full vaccination, albeit that the programme has focussed on rollout by age cohort, starting with those most at risk of serious illness or death.

There\’s the simple fact that none of the vaccines is, as yet, approved for use in young people under 12, and not all are yet approved for 12-17 year-olds. In any case, there does not appear to be a policy decision on actually vaccinating the under-18s. Here, we know that younger people are much less susceptible to acute illness than those who are older. However, they can (and do) form a significant vector for transmission across the wider population. There is also emerging evidence that younger people are more prone to long-term \’Long Covid\’ effects, especially neurological, from Covid-19.

Then there are those who genuinely can\’t tolerate a vaccine. They remain as vulnerable as ever, subject to the virology of the current variant and to their level of contact with the wider population who – even when vaccinated – are capable of transmitting the virus.

Finally, there are those who choose, from whatever rational (there are a few) ideological or delusional position, not to have a vaccine. For this cohort, it is likely that they will continue to demonstrate a higher likelihood of transmission to others, especially vulnerable groups, and will themselves become an increasing proportion of the burden on the healthcare system. However, the transmission argument only applies if inoculation proves to reduce viral shedding by a reasonable amount. If it will turn out that this is not the case, the primary reason for vaccination remains the dramatic reduction in symptomacity, which actually is what a vaccine is designed for.

We do now appear to be approaching a crossover point where sufficient of the population are protected against current variants that a degree of what we used to call normality can be resumed, and where, for most, the simple fact that the virus is still spreading rapidly doesn\’t matter so much.

However, we\’re not yet seeing any plausible policy or process for protecting these vulnerable remaining groups – pregnant women, the vaccine intolerant – typically through allergy or temporary or permanent immunocompromise – as well as those under 18, all of whom should be the highest priority in any plan for further relaxation.

About us: Intelligent Reality is a data intelligence company, using emergent approaches and inferential AI to provide daily analyses and forecasts for Covid-19, currently for the UK. We’re based in Scotland and Germany, and supported by the udu team in the USA. Together we have brought together a highly experienced team of data scientists, designers and epidemiologists to address some of the key problems we’ve seen with the generation and use of pandemic data to support decision making for public policy.